|

http://worldtraining.net/Oz.htm See also: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: A Monetary Reformer’s

Brief Symbol Glossary [ [[ |

[ Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0dUgOeAG3Y OR https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sboh-_w43W8

] Source: http://www.themoneymasters.com/the-wonderful-wizard-of-oz-a-monetary-reformers-brief-symbol-glossary/ ] The

following is a compilation of several views of the monetary reform symbolism

used by L. Frank Baum in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Interpretations vary,

particularly on the lesser figures, but this will give the readers good

reference points to begin their consideration of the matter. Was the symbolism

consciously or subconsciously employed? We cannot know with certainty, nor does

it really matter. What matters is that Baum understood the issues involved and

employed them in Oz. Millions of Americans have seen Oz, generally several

times. Knowingly or not, Oz has given us a key to understanding the solutions

to the economic issues we face in our time if we could only accept that we have

had the power to regain our bank-mortgaged homes all along, just as Dorothy

did. Remember: “There’s no place like home.”

Dorothy –

everyman and woman, a simple, Populist character from the heartland of American

Populism, Kansas.

Scarecrow –

farmers, agricultural workers, ignorant of many city things but honest and able

to understand things with a little education. A strong supporter of Dorothy

(Populism).

Tin Man – industrial workers; a woodchopper whose

entire body has been replaced with metal parts, thus dehumanized by machinery

(robot-like with no heart) in need of oil (liquidity/money) to work, otherwise

unemployed (he was idle for a year) without oil.

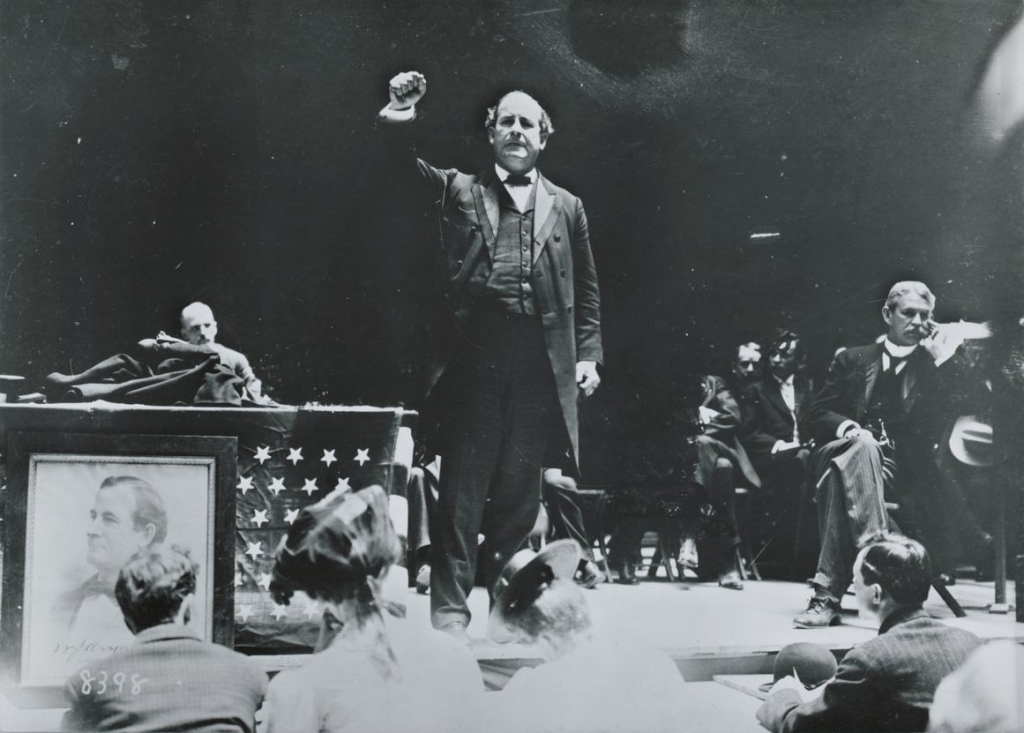

Cowardly Lion –

Wm. Jenning Bryan, a famous politician and Populist Presidential candidate in

1896 and 1900 (Oz was written in 1900) for monetary reform and a terrific

orator (i.e., roar). Bryan was attacked as being somewhat cowardly for not

supporting the US war with Spain. As a Populist Presidential candidate he sought

to go to the capitol city – the Emerald city. Bryan’s famous “Cross of

Gold” speech is posted below. Ruby

Slippers – these are silver in the book. Hollywood changed them to ruby

red to take advantage of the new Technicolor used in the movie version,

evidently ignorant of the meaning of the silver. Byran and many other

Greenbackers (monetary reformers supporting use of debt-free US Notes like

Lincoln’s Greenbacks to increase the money supply and thereby end the

depression then) shifted their tactics to the promotion of adding silver to the

lawful coinage of America (i.e., to promoting a bi-metallic standard rather

than the theoretically purer, fiat Greenbacks) when they realized they could

thereby gain the backing of the powerful silver mining interests and still

increase the money supply (without debt) to more than just gold. Silver thus

became a symbol of overcoming a purely gold standard with the limited money

supply and banker control that resulted in. Hence the silver slippers were

extremely important in the book, as silver coin was in reality.

Kansas –

a Populist stronghold, home of Dorothy, symbolized the national heartland.

Cyclone (toronado) –

the free silver movement, compared at the time to a political “cyclone” that

swept Kansas, Nebraska and the heartland and aimed at Washington; also the

depression of the 1890’s which was compared to a “cyclone” in a famous monetary

primer of the time and which robbed people of their homes and farms.

Oz –

corresponds to standard measure of gold ounce – “oz”; America, where the

gold oz standard held sway, but where the use of the silver oz (slippers) could

free the slaves.

Emerald City – political center of Oz /Washinton

D.C. To get there a politician had to take the gold way (gold standard);

everyone there was forced to wear “green spectacles” – to see the world

through another color (green) of money. This illusion upheld the Wizard’s

power.

Glinda, the Good Witch of the South – the US South, which

solidly supported Bryan and reform, as did much of the North (home of the other

good witch in the book). The East and West (homes of the bad witches) supported

McKinley.

Good Witch of the

North – Bryan’s Populist supporters in the North and Northwest. The South

and North largely supporter Bryan in his Presidential campaign; the wicked East

and West supported McKinley who was for the gold standard

Wicked Witch of the

East – Wall Street bankers in NY, led by J.P. Morgan. President Grover

Cleveland (of NY) was their pro-gold standard candidate.

Wicked Witch of the

West – draught and/or J.D. Rockefeller, by then a Cleveland banker (still

viewed as “out West” from a NY perspective). President Wm. McKinley (a gold

standard supporter from Ohio) was his candidate. She was a one-eyed witch ,

i.e., opposed to the two metal bi-metallic system; in the book she enslaves

Winkies in the West much as the Wicked Witch in the East enslaves the

Munchkins; dissolved by water symbolizing real water curing draught and/or

liquidity ending the depression.

Wizard – a

charlatan who politician-like can change forms in the book and who tricked the

citizens of Oz into believing he is all powerful. Sometimes compared to a

behind-the-scenes manipulator “pulling-the-strings” of politicians just as Wall

Street’s bankers do today. Mark Hanna, such a man at the time, has been

suggested as the real life model for the Wizard. He said “There are two things

that are important in politics. The first is money and I can’t remember the

second”. Such an all-powerful view of money is a deceit noted under the word “Emerald

City,” above. Baum was well informed – he knew banks manipulated

politicians and the people and commonly used deceit to fool them into

submission. $700 billion or we face a “global financial meltdown” ring a bell?

Bankers create money – a trickery certainly known to Baum.

Yellow Brick Road –

the gold way or standard, composed of gold bricks.

Munchkins – the

common people of the East, [wage] slaves to the Wicked Witch of the East.

Deadly Poppy Field –

the anti-imperialism movement of the late 1890’s which reformers felt was

distracting Byran from monetary reform (putting him to sleep on the issue),

saved from that fate by the mice (the little people, Populist supporters).

Color themes, the

colors of money: gold (coin), silver (coin), green (paper greenbacks)

Winged Monkey’s –

Plains Indians: “Once we were free people living happily in he forest.” –

monkey leader. Like the winkies and munchkins, enslaved by the wicked witch and

not freed until water (liquidity) destroys her hold on them.

Yellow Brick Road –

the gold way, gold standard (yellow bricks)

Dorothy’s “party” –

party is used 8 times referring to Dorothy’s followers, a reference to the

Populist Party, trying to get Dorothy to the capitol city (Washington).

Oil –

liquidity, priming the pump of the economy, enabling employment of the

unemployed (the Tin Man had been idle for a year without it).

Toto – the

prohibitionists (“with Toto trotted along soberly behind her”), a movement

which followed the bi-metallist Populist Party.

Kalidahs –

predators in the book probably representing newspaper reporters who

overwhelmingly opposed to Byran as their papers were heavily influenced by

banking and business interests.

Stork – a female stork in the book

referring to the women’s sufferage movement which supported the Populists.

* * *

William Jenning Bryan’s Cross of Gold

Speech

The most famous

speech in American political history was delivered by William Jennings Bryan on

July 9, 1896, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The issue was whether

to endorse the free coinage of silver at a ratio of silver to gold of 16 to 1.

(This inflationary measure would have increased the amount of money in

circulation and aided cash-poor and debt-burdened farmers.) After speeches on

the subject by several U.S. Senators, Bryan rose to speak. The

thirty-six-year-old former Congressman from Nebraska aspired to be the

Democratic nominee for president, and he had been skillfully, but quietly,

building support for himself among the delegates. His dramatic speaking style

and rhetoric roused the crowd to a frenzy. The response, wrote one reporter, “came

like one great burst of artillery.” Men and women screamed and waved their hats

and canes. “Some,” wrote another reporter, “like demented things, divested

themselves of their coats and flung them high in the air.” The next day the

convention nominated Bryan for President on the fifth ballot. The full text of

William Jenning Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” speech appears below.* * *

I

would be presumptuous, indeed, to present myself against the distinguished

gentlemen to whom you have listened if this were but a measuring of ability;

but this is not a contest among persons. The humblest citizen in all the land

when clad in the armor of a righteous cause is stronger than all the whole

hosts of error that they can bring. I come to speak to you in defense of a

cause as holy as the cause of liberty—the cause of humanity. When this

debate is concluded, a motion will be made to lay upon the table the resolution

offered in commendation of the administration and also the resolution in

condemnation of the administration. I shall object to bringing this question

down to a level of persons. The individual is but an atom; he is born, he acts,

he dies; but principles are eternal; and this has been a contest of principle.

Never before in the

history of this country has there been witnessed such a contest as that through

which we have passed. Never before in the history of American politics has a

great issue been fought out as this issue has been by the voters themselves.

On the 4th of March,

1895, a few Democrats, most of them members of Congress, issued an address to

the Democrats of the nation asserting that the money question was the paramount

issue of the hour; asserting also the right of a majority of the Democratic

Party to control the position of the party on this paramount issue; concluding

with the request that all believers in free coinage of silver in the Democratic

Party should organize and take charge of and control the policy of the

Democratic Party. Three months later, at Memphis, an organization was

perfected, and the silver Democrats went forth openly and boldly and

courageously proclaiming their belief and declaring that if successful they

would crystallize in a platform the declaration which they had made; and then

began the conflict with a zeal approaching the zeal which inspired the

crusaders who followed Peter the Hermit. Our silver Democrats went forth from

victory unto victory, until they are assembled now, not to discuss, not to

debate, but to enter up the judgment rendered by the plain people of this

country.

But in this contest,

brother has been arrayed against brother, and father against son. The warmest

ties of love and acquaintance and association have been disregarded. Old

leaders have been cast aside when they refused to give expression to the

sentiments of those whom they would lead, and new leaders have sprung up to

give direction to this cause of freedom. Thus has the contest been waged, and

we have assembled here under as binding and solemn instructions as were ever

fastened upon the representatives of a people.e been glad to compliment the

gentleman from New York [Senator Hill], but we knew that the people for whom we

speak would never be willing to put him in a position where he could thwart the

will of the Democratic Party. I say it was not a question of persons; it was a

question of principle; and it is not with gladness, my friends, that we find

ourselves brought into conflict with those who are now arrayed on the other

side. The gentleman who just preceded me [Governor Russell] spoke of the old

state of Massachusetts. Let me assure him that not one person in all this

convention entertains the least hostility to the people of the state of

Massachusetts.

But we stand here

representing people who are the equals before the law of the largest cities in

the state of Massachusetts. When you come before us and tell us that we shall

disturb your business interests, we reply that you have disturbed our business interests

by your action. We say to you that you have made too limited in its application

the definition of a businessman. The man who is employed for wages is as much a

businessman as his employer. The attorney in a country town is as much a

businessman as the corporation counsel in a great metropolis. The merchant at

the crossroads store is as much a businessman as the merchant of New York. The

farmer who goes forth in the morning and toils all day, begins in the spring

and toils all summer, and by the application of brain and muscle to the natural

resources of this country creates wealth, is as much a businessman as the man

who goes upon the Board of Trade and bets upon the price of grain. The miners

who go 1,000 feet into the earth or climb 2,000 feet upon the cliffs and bring

forth from their hiding places the precious metals to be poured in the channels

of trade are as much businessmen as the few financial magnates who in a

backroom corner the money of the world.

We come to speak for

this broader class of businessmen. Ah. my friends, we say not one word against

those who live upon the Atlantic Coast; but those hardy pioneers who braved all

the dangers of the wilderness, who have made the desert to blossom as the rose—those

pioneers away out there, rearing their children near to nature’s heart, where

they can mingle their voices with the voices of the birds—out there where

they have erected schoolhouses for the education of their children and churches

where they praise their Creator, and the cemeteries where sleep the ashes of

their dead—are as deserving of the consideration of this party as any

people in this country.

It is for these that

we speak. We do not come as aggressors. Our war is not a war of conquest. We

are fighting in the defense of our homes, our families, and posterity. We have

petitioned, and our petitions have been scorned. We have entreated, and our

entreaties have been disregarded. We have begged, and they have mocked when our

calamity came.

We beg no longer; we

entreat no more; we petition no more. We defy them!

The gentleman from

Wisconsin has said he fears a Robespierre. My friend, in this land of the free

you need fear no tyrant who will spring up from among the people. What we need

is an Andrew Jackson to stand as Jackson stood, against the encroachments of

aggregated wealth.

They tell us that

this platform was made to catch votes. We reply to them that changing

conditions make new issues; that the principles upon which rest Democracy are

as everlasting as the hills; but that they must be applied to new conditions as

they arise. Conditions have arisen and we are attempting to meet those

conditions. They tell us that the income tax ought not to be brought in here;

that is not a new idea. They criticize us for our criticism of the Supreme Court

of the United States. My friends, we have made no criticism. We have simply

called attention to what you know. If you want criticisms, read the dissenting

opinions of the Court. That will give you criticisms.

They say we passed an

unconstitutional law. I deny it. The income tax was not unconstitutional when

it was passed. It was not unconstitutional when it went before the Supreme

Court for the first time. It did not become unconstitutional until one judge

changed his mind; and we cannot be expected to know when a judge will change

his mind.

The income tax is a

just law. It simply intends to put the burdens of government justly upon the

backs of the people. I am in favor of an income tax. When I find a man who is

not willing to pay his share of the burden of the government which protects

him, I find a man who is unworthy to enjoy the blessings of a government like

ours.

He says that we are

opposing the national bank currency. It is true. If you will read what Thomas

Benton said, you will find that he said that in searching history he could find

but one parallel to Andrew Jackson. That was Cicero, who destroyed the

conspiracies of Cataline and saved Rome. He did for Rome what Jackson did when

he destroyed the bank conspiracy and saved America.

We say in our

platform that we believe that the right to coin money and issue money is a

function of government. We believe it. We believe it is a part of sovereignty

and can no more with safety be delegated to private individuals than can the

power to make penal statutes or levy laws for taxation.

Mr. Jefferson, who

was once regarded as good Democratic authority, seems to have a different

opinion from the gentleman who has addressed us on the part of the minority.

Those who are opposed to this proposition tell us that the issue of paper money

is a function of the bank and that the government ought to go out of the

banking business. I stand with Jefferson rather than with them, and tell them,

as he did, that the issue of money is a function of the government and that the

banks should go out of the governing business.

They complain about

the plank which declares against the life tenure in office. They have tried to

strain it to mean that which it does not mean. What we oppose in that plank is

the life tenure that is being built up in Washington which establishes an

office-holding class and excludes from participation in the benefits the

humbler members of our society. . . .

Let me call attention

to two or three great things. The gentleman from New York says that he will propose

an amendment providing that this change in our law shall not affect contracts

which, according to the present laws, are made payable in gold. But if he means

to say that we cannot change our monetary system without protecting those who

have loaned money before the change was made, I want to ask him where, in law

or in morals, he can find authority for not protecting the debtors when the act

of 1873 was passed when he now insists that we must protect the creditor. He

says he also wants to amend this platform so as to provide that if we fail to

maintain the parity within a year that we will then suspend the coinage of

silver. We reply that when we advocate a thing which we believe will be

successful we are not compelled to raise a doubt as to our own sincerity by

trying to show what we will do if we are wrong.

I ask him, if he will

apply his logic to us, why he does not apply it to himself. He says that he

wants this country to try to secure an international agreement. Why doesn’t he

tell us what he is going to do if they fail to secure an international

agreement. There is more reason for him to do that than for us to expect to

fail to maintain the parity. They have tried for thirty years—thirty

years—to secure an international agreement, and those are waiting for it

most patiently who don’t want it at all.

Now, my friends, let

me come to the great paramount issue. If they ask us here why it is we say more

on the money question than we say upon the tariff question, I reply that if

protection has slain its thousands the gold standard has slain its tens of

thousands. If they ask us why we did not embody all these things in our

platform which we believe, we reply to them that when we have restored the

money of the Constitution, all other necessary reforms will be possible, and

that until that is done there is no reform that can be accomplished.

Why is it that within

three months such a change has come over the sentiments of the country? Three

months ago, when it was confidently asserted that those who believed in the

gold standard would frame our platforms and nominate our candidates, even the

advocates of the gold standard did not think that we could elect a President;

but they had good reasons for the suspicion, because there is scarcely a state

here today asking for the gold standard that is not within the absolute control

of the Republican Party.

But note the change.

Mr. McKinley was nominated at St. Louis upon a platform that declared for the

maintenance of the gold standard until it should be changed into bimetallism by

an international agreement. Mr. McKinley was the most popular man among the

Republicans ; and everybody three months ago in the Republican Party prophesied

his election. How is it today? Why, that man who used to boast that he looked

like Napoleon, that man shudders today when he thinks that he was nominated on

the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. Not only that, but as he listens he

can hear with ever increasing distinctness the sound of the waves as they beat

upon the lonely shores of St. Helena.

Why this change? Ah,

my friends. is not the change evident to anyone who will look at the matter? It

is because no private character, however pure, no personal popularity, however

great, can protect from the avenging wrath of an indignant people the man who

will either declare that he is in favor of fastening the gold standard upon

this people, or who is willing to surrender the right of self-government and

place legislative control in the hands of foreign potentates and powers. . . .

We go forth confident

that we shall win. Why? Because upon the paramount issue in this campaign there

is not a spot of ground upon which the enemy will dare to challenge battle.

Why, if they tell us that the gold standard is a good thing, we point to their

platform and tell them that their platform pledges the party to get rid of a

gold standard and substitute bimetallism. If the gold standard is a good thing,

why try to get rid of it? If the gold standard, and I might call your attention

to the fact that some of the very people who are in this convention today and

who tell you that we ought to declare in favor of international bimetallism and

thereby declare that the gold standard is wrong and that the principles of

bimetallism are better—these very people four months ago were open and

avowed advocates of the gold standard and telling us that we could not

legislate two metals together even with all the world.

I want to suggest

this truth, that if the gold standard is a good thing we ought to declare in

favor of its retention and not in favor of abandoning it; and if the gold

standard is a bad thing, why should we wait until some other nations are

willing to help us to let it go?

Here is the line of

battle. We care not upon which issue they force the fight. We are prepared to

meet them on either issue or on both. If they tell us that the gold standard is

the standard of civilization, we reply to them that this, the most enlightened

of all nations of the earth, has never declared for a gold standard, and both the

parties this year are declaring against it. If the gold standard is the

standard of civilization, why, my friends, should we not have it? So if they

come to meet us on that, we can present the history of our nation. More than

that, we can tell them this, that they will search the pages of history in vain

to find a single instance in which the common people of any land ever declared

themselves in favor of a gold standard. They can find where the holders of

fixed investments have.

Mr. Carlisle said in

1878 that this was a struggle between the idle holders of idle capital and the

struggling masses who produce the wealth and pay the taxes of the country; and

my friends, it is simply a question that we shall decide upon which side shall

the Democratic Party fight. Upon the side of the idle holders of idle capital,

or upon the side of the struggling masses? That is the question that the party

must answer first; and then it must be answered by each individual hereafter.

The sympathies of the Democratic Party, as described by the platform, are on

the side of the struggling masses, who have ever been the foundation of the

Democratic Party.

There are two ideas

of government. There are those who believe that if you just legislate to make

the well-to-do prosperous, that their prosperity will leak through on those

below. The Democratic idea has been that if you legislate to make the masses

prosperous their prosperity will find its way up and through every class that

rests upon it.

You come to us and

tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard. I tell you

that the great cities rest upon these broad and fertile prairies. Burn down

your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by

magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every

city in the country.

My friends, we shall

declare that this nation is able to legislate for its own people on every

question without waiting for the aid or consent of any other nation on earth,

and upon that issue we expect to carry every single state in the Union.

I shall not slander

the fair state of Massachusetts nor the state of New York by saying that when

citizens are confronted with the proposition, “Is this nation able to attend to

its own business?”—I will not slander either one by saying that the

people of those states will declare our helpless impotency as a nation to

attend to our own business. It is the issue of 1776 over again. Our ancestors,

when but 3 million, had the courage to declare their political independence of

every other nation upon earth. Shall we, their descendants, when we have grown

to 70 million, declare that we are less independent than our forefathers? No,

my friends, it will never be the judgment of this people. Therefore, we care

not upon what lines the battle is fought. If they say bimetallism is good but

we cannot have it till some nation helps us, we reply that, instead of having a

gold standard because England has, we shall restore bimetallism, and then let

England have bimetallism because the United States have.

If they dare to come

out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we shall

fight them to the uttermost, having behind us the producing masses of the

nation and the world. Having behind us the commercial interests and the

laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands

for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow

of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of

gold.”