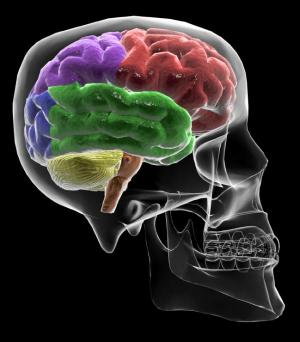

Brain

Images Make Cognitive Research More Believable

Science Daily — Oct 8, 2007 http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/10/071002151837.htm

People

are more likely to believe findings from a neuroscience study when the report

is paired with a colored image of a brain as opposed to other representational

images of data such as bar graphs, according to a new Colorado State University

study.

People

are more likely to believe findings from a neuroscience study when the report

is paired with a colored image of a brain as opposed to other representational

images of data such as bar graphs, according to a new Colorado State University

study. (Credit: iStockphoto/Aaron Kondziela)

Persuasive

influence on public perception

Scientists

and journalists have recently suggested that brain images have a persuasive

influence on the public perception of research on cognition. This idea was

tested directly in a series of experiments reported by David McCabe, an

assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at Colorado State, and his

colleague Alan Castel, an assistant professor at University of California-Los

Angeles. The forthcoming paper, to be published in the journal Cognition, was

recently published online.

"We

found the use of brain images to represent the level of brain activity

associated with cognitive processes clearly influenced ratings of scientific

merit," McCabe said. "This sort of visual evidence of physical

systems at work is typical in areas of science like chemistry and physics, but

has not traditionally been associated with research on cognition.

"We

think this is the reason people find brain images compelling. The images

provide a physical basis for thinking."

Brain

images compelling

In

a series of three experiments, undergraduate students were either asked to read

brief articles that made fictitious and unsubstantiated claims such as

"watching television increases math skills," or they read a real

article describing research showing that brain imaging can be used as a lie

detector.

When

the research participants were asked to rate their agreement with the

conclusions reached in the article, ratings were higher when a brain image had

accompanied the article, compared to when it did not include a brain image or

included a bar graph representing the data.

This

effect occurred regardless of whether the article described a fictitious,

implausible finding or realistic research.

Conclusions

often oversimplified and misrepresented

"Cognitive

neuroscience studies which appear in mainstream media are often oversimplified

and conclusions can be misrepresented," McCabe said. "We hope that

our findings get people thinking more before making sensational claims based on

brain imaging data, such as when they claim there is a 'God spot' in the

brain."

Article:

"Seeing is believing: The effect of brain images on judgments and

scientific reasoning."

Note: This story has been

adapted from material provided by Colorado State University.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/images/2007/10/071002151837.jpg